3

Stone Carving Calligraphy

It's said in “Wenxin Diaolong”, or “Dragon-Carving and the Literary Mind” that “Replacing metal with stone, and the latter equally endures forever.” Our ancestors first used metal and stone to preserve the content of writings. Stone's durability, chiseling and engraving ease, ample surface area, flexibility in placement, and simple preservation led to its gradual preference over bronze for historical inscriptions.

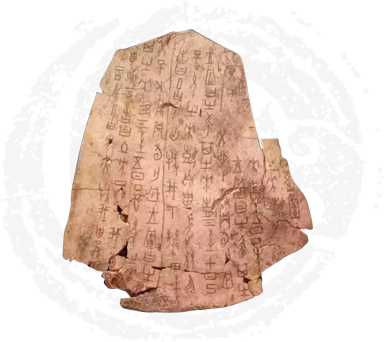

○ Stone Drum Scripts

Stone inscriptions were first seen on stone chimes and jade artifacts during the Shang Dynasty. During the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period, a small number of stone carving works emerged, significantly longer in length, among which the most iconic were stone drum inscriptions. Known as the ancestors of stone carvings, they were inscribed on ten drum-shaped granite stones, hence the name “stone drum scripts”. On each stone drum, there is a quatrain recording the Dukes of Qin’s hunting activities. They represent a transitional and indefinite script between Large and Small Seal scripts, holding a pivotal position in the study of Zhou and Qin history, epigraphy, philology, literary history, and calligraphy.

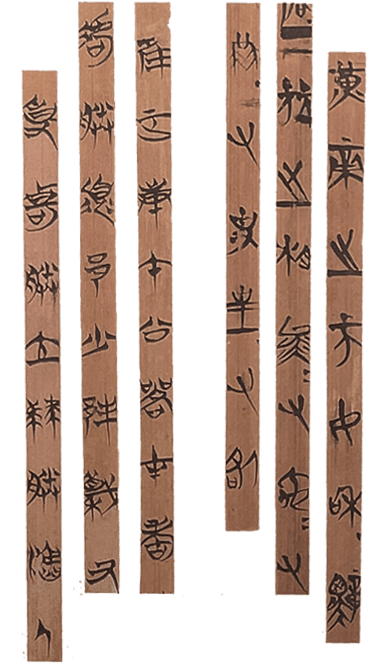

○ Dengci Temple Stele

The full name of the “Dengci(meaning equally merciful) Temple Stele” is “Dengci Temple Stele by the Great Tang Emperor”. It is said to have been written by Yan Shigu(a minister, Confucian scholar and linguist) of the Tang Dynasty and has a history of more than 1300 years. The inscription records the event where Emperor Li Shimin, with only a few thousand elite soldiers, defeated rebel leader Dou Jiande’s army of 100,000 at Hulao Pass, and the reason for the subsequent establishment of the temple and stele, making it an important historical document. The layout of the inscriptions is clear and well-arranged, and has been praised by contemporary calligrapher Ouyang Zhongshi as “ An excellent learning resource with ample room for maneuver, from the Wei Steles to the mature Tang regular script.”